By Eric Boysen

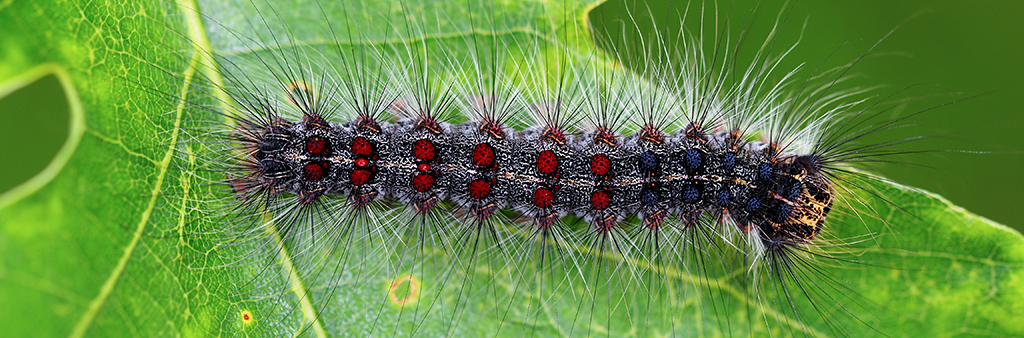

Populations of the invasive European spongy moth (Lymantria dispar dispar) expanded in the summer of 2020 across a broad area in Southern Ontario. spongy moths can easily spread across long distances when egg masses are laid on surfaces such as cars and campers. And local distribution occurs once they hatch, as the new larvae hang on silken threads and are dispersed locally by the wind. By the end of their feeding cycle in early July 2020, the damage was described by the Forest Health team at the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF) as “moderate – severe”. Egg mass surveys over the fall and winter indicated that the population would be as high again in 2021.

Spongy moth larvae feed on a wide range of forest tree species. The impacts of defoliation are worsened when trees are already suffering from other effects prior to defoliation (e.g. previous damage from other insects like the forest tent caterpillar, or droughts, etc).

Impacts

Not all trees are affected to the same degree. Hardwoods such as poplars, birches, basswood and willows seem to be able to shake off the impact, and you will hardly notice the damage by late summer. Other hardwoods such as oaks, maples, beech, fruit trees, hickories and elms will also refoliate. But the new leaves may not be as large or numerous as the first crop. As well, developing flower and seed may be aborted as the trees shift their energy resources to producing new leaves. Trees which were already under stress may suffer crown die-back, or even total mortality after repeated defoliations. Other hardwood species such as ashes, catalpa (non-native), sycamore and tulip poplar do not seem to be eaten by the spongy moth.

The most concerning impact will be on conifers. White pine, white and blue spruce (non-native), hemlock and balsam fir are all susceptible. The larvae feed on the older foliage and can strip a mature white pine of all needles in one season. They cannot re-foliate and must rely on the photosynthesis by any remaining needles to sustain their growth. Two years of successive defoliation will cause the death of these conifers.

Control

While there are a number of tactics a homeowner can take at an individual tree or backyard level, most woodlot owners have to wait and hope for the population to collapse. https://www.ontariowoodlot.com/images/Gypsy%20Moth%20Information%20-%20April%202021.pdf?_t=1619791413

The NPV (nucleopolyhedrosis virus) is usually the most important factor in the collapse of gypsy moth outbreaks in North America. The virus is always present in a spongy moth population and can be transmitted from the female moth to her offspring. It spreads naturally through the spongy moth population, especially when caterpillars are abundant. During a spongy moth outbreak (i.e. high population), caterpillars are more susceptible to this virus because they are stressed from competing with one another for food and space. Typically, 1 to 2 years after an outbreak begins, the NPV disease causes a major die-off of caterpillars.

Another natural killer of Spongy moth larvae is fungus Entomophaga maimaiga. Fungal spores that overwinter in the soil will infect young caterpillars early in the summer. When the young caterpillars die, their bodies produce windblown spores that can spread and infect older caterpillars. Within several days, the cadavers fall to the soil and disintegrate, releasing the spores that will overwinter back into the soil. The fungus is most active in cooler, wetter periods.

Some birds, mammals and rodents will also feed on the growing larvae – but this type of predation is unlikely to cause a population decline. Basically, we must wait for them to eat themselves out of house and home, and be aware that the impacts of this defoliation could be seen for a number of years after the caterpillars have gone.

The following graphic demonstrates the population level dynamics for Spongy Moth:

Source: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resource

Homeowners and woodlot owners are encouraged to protect your trees in whatever way is practical from spongy moth, and unfortunately many other stressors including climate change (heat, drought, severe weather, etc), other invasive insects, diseases, invasive plants, and poor woodlot management and practices (high grading, etc). Learn and know what a healthy tree looks like, so that you can identify trees that are under stress. Continuously monitoring the health of your trees will help you decide what management actions to take to maintain the resilience of your forest.

“The Spongy moth caterpillars are back but in greater numbers this year compared to last year. The FGCA too has been dealing with the effects of the spongy moth defoliation damage but this year the numbers have grown significantly across Ontario.” – Becky Agnew, Forest Technician, FGCA

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.